My first year with 4x5

The desire to work with 4×5 did not come suddenly. It developed alongside my growing interest in analog photography—from 35 mm with the Pentax KM, to medium format with the Mamiya 645, and eventually to the question of how much image quality, materiality, and presence really matter to me.

I don’t want to focus here on the often-mentioned idea that large format simply means “working more slowly.” While that is true, it doesn’t describe the core of my motivation. What drew me in was the physical presence of these cameras—their size, their mechanics, their tactility. I had never held anything comparable before. They demand attention even before a photograph is made.

Around the same time, Instagram gradually lost its relevance for me. I continued to share analog work there, but the rhythm of the platform, the dominance of reels, AI-generated content, and the increasing visual exaggeration of images created distance. Without judgment—none of this is wrong. It simply isn’t the way I want to work.

Even during my digital phase, I repeatedly came across the work of Ben Horn. His sensitivity to quiet details is impressive, though his visual world is not mine. The real fascination with 4×5, however, began when I started watching the videos of Kyle McDougall. His calm approach and careful choice of subjects showed me that this kind of photography does not need to be loud to be effective.

Gradually, the idea formed to use an old technique to photograph spaces and objects that have themselves grown quiet. As I was already increasingly drawn to black-and-white photography, the step toward analog large format felt like a natural continuation.

At the beginning, there was a simple question: which camera should I buy? A used one, or a newly built one. Old cameras undoubtedly have their own charm. But it quickly became clear to me that I lacked the experience to deal confidently with repairs or technical problems. The thought of being stuck if something went wrong held me back.

That immediately led to the next uncertainty: how much money was I willing—and able—to invest from the start. A more expensive decision would have put greater strain on my budget. A more affordable option seemed sensible, especially since it did not limit me visually. It mattered to me that the camera felt right. The way it looked played a role—perhaps more than I initially wanted to admit.

Looking back, this was not a technical decision. It was an attempt to create a framework in which I could focus on the image, without constantly worrying about defects, costs, or wrong decisions.

The first shoot took place in a nearby park. I found my first subject quickly. Then the setup began. Everything carefully, deliberately. Don’t make a mistake. Align the rear standard, align the front standard. Open the aperture, set the composition, focus under the dark cloth. Measure the light. Set the aperture—and most importantly, close it again. Set the shutter speed. Attach the mechanical cable release. Expose.

Afterwards, I packed up the camera and moved on.

Only while folding the camera did the thought occur: wait a moment—did you just make your first beginner’s mistake? And what a mistake it was. Despite all the concentration, I had forgotten to insert the film holder in front of the ground glass. The dark slide didn’t even come into play.

At that moment it became clear: even maximum attention does not prevent mistakes. And that was fine. I never expected everything to work perfectly the first time.

Loading the film holders also proved to be less straightforward than I had anticipated. It didn’t go smoothly, but at first I accepted that calmly. The first negatives were planned as losses. I needed material to practice, and mistakes were part of that.

The next turning point came when I took the first negatives in for development. Only then did I realize what practice means at this scale. Development and scanning were expensive—far more expensive than I was used to from smaller formats. So I initially chose development only. Scanning, I decided, I would do myself.

That led directly to the next question: if I was already scanning myself, why not develop the film as well? Initially, I had wanted to avoid that in order to reduce potential sources of error at the beginning. But it became clear that responsibility cannot be postponed here. If I wanted to take this path, I had to take it fully from the start.

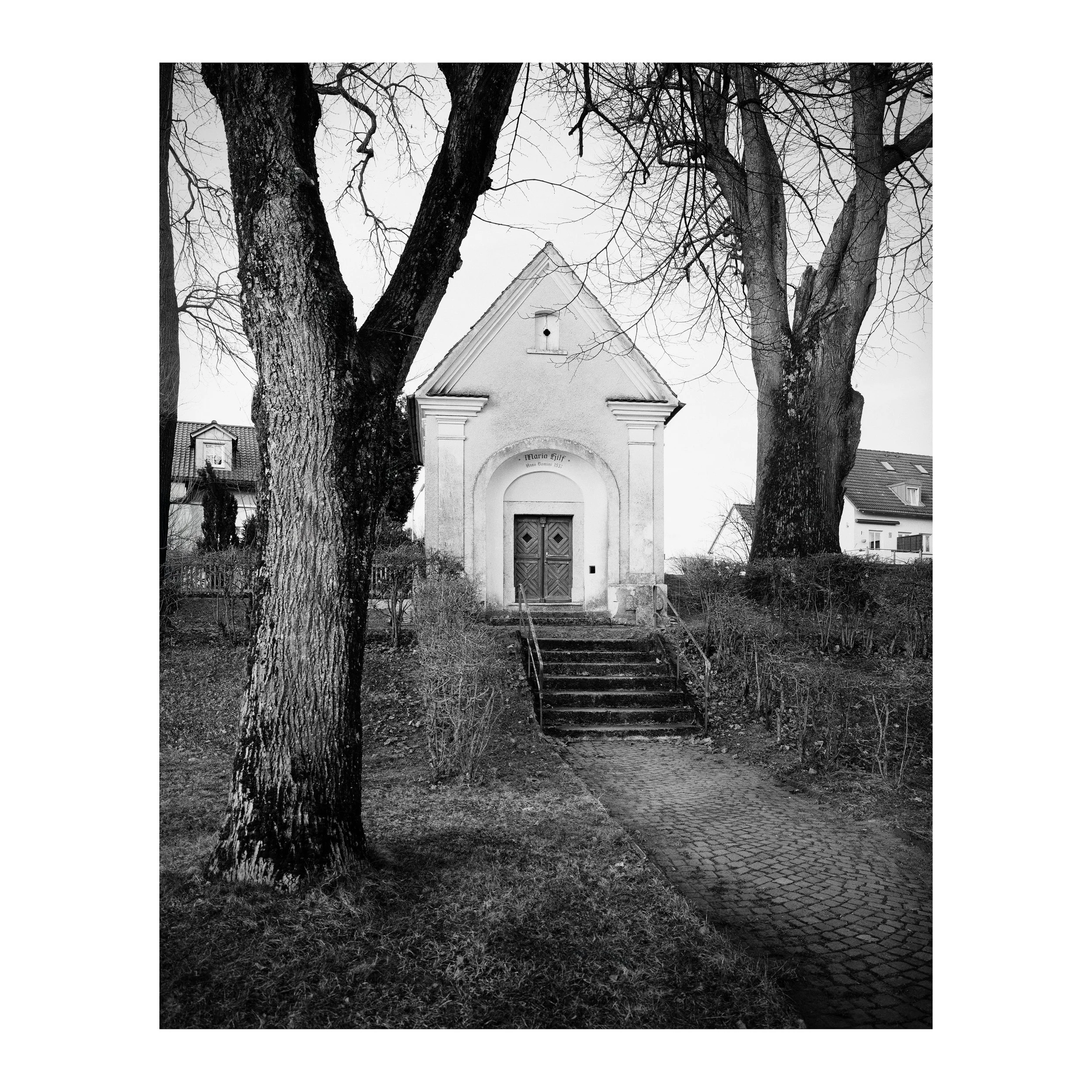

After these first experiences, I didn’t want to continue making isolated images. I needed a framework. The plan was modest: five photographs under the working title Quiet Spaces. No grand concept—more an attempt to give structure to what I was learning and to work with greater intention.

During those first photographs, it became clear how well this theme connected with my previous work. The quiet approach, careful observation, the deliberate omission of anything unnecessary—all of it found a place here. The camera was no longer an end in itself, but a means.

What began as a small project quickly became more. Quiet Spaces did not remain a closed experiment, but developed into a long-term undertaking. Not because everything suddenly worked, but precisely because so much remained unresolved.

Now, after almost a year, I realize that I am still learning. And that applies to every aspect of large format photography. Metering light, composing on the ground glass, focusing, using movements—much of this is still at the beginning. The choice of which film fits which situation, and how different developers influence the result, remains an ongoing process.

That is exactly what makes this way of working so compelling to me. There is no point of arrival—only the willingness to continue. With each image, each decision, and with the understanding that the coming year will be, above all, another year of learning.